Written by Ing. Andrea Trombetta

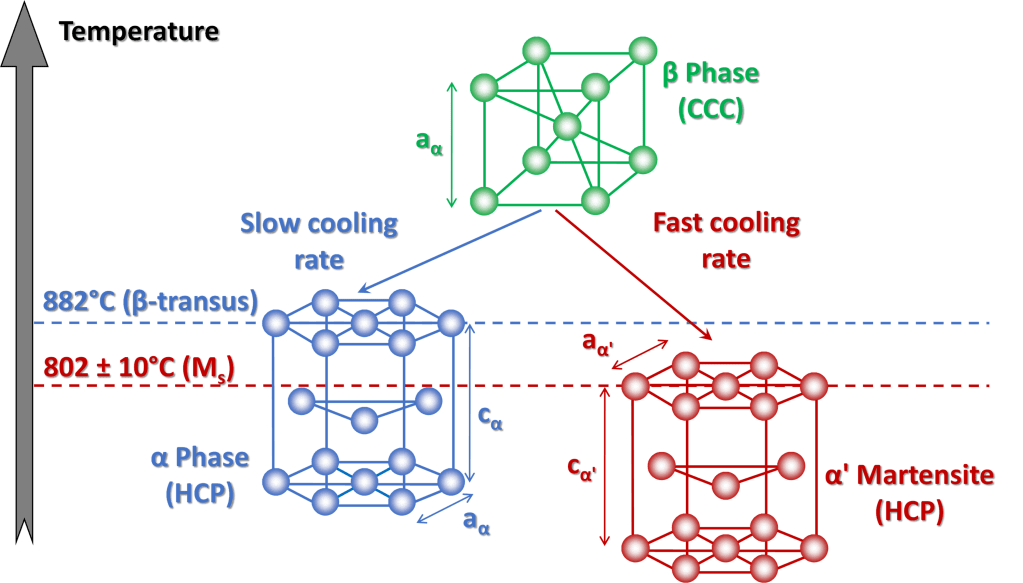

Titanium shows an allotropic transformation through which the crystal lattice changes from hexagonal close packed (HCP) at room temperature to body centered cubic (CCC) at high temperatures. For pure titanium, the HCP structure, or α-phase, is stable up to 882°C, temperature which is commonly defined as “β-transus”. At higher temperatures, the structure becomes CCC, or β phase, which is maintained up to 1670°C, a value which corresponds to the melting point of pure titanium.

In titanium alloys the β-transus temperature strongly depends on the specific chemical composition: alloy elements are divided into α-stabilizers, such as Al, N and O, which raise β-transus temperature, β-stabilizers such as Mo, V, Cr and Fe, which decrease β-transus, and neutral, Sn and Zr, which do not significantly affect β-transus. More in general, for a specific titanium alloy, beta transus temperature is defined as the temperature above which the microstructure is completely made up of beta phase.

In titanium, β-α phase transition, which is schematically illustrated in Figure 1, occurs during cooling from high temperature only if the cooling rate is slow enough to allow the transport of atoms by diffusion, thus determining the transformation of CCC lattice of β-phase into HCP lattice of α-phase.

At very high cooling rates, for example quenching with water, the transport of atoms by diffusion is totally prevented; however, a phase transition still occurs through a martensitic-type mechanism, which involves the coordinated movement of some atoms, thus allowing the formation of a structure with an HCP crystal lattice called α’ martensite (or “alpha prime”).

As for steel quenching, the formation of α’ martensite in titanium and its alloys is characterized by the existence of a well-defined crystallographic orientation relationship between parent and product phases, by the presence of an invariant crystallographic plane, also known as “habit plane” by an increase in volume with consequent associated strains, by the presence of a start (Ms) and finish (Mf) temperature of the martensitic transformation, which are lower than β-transus (for pure titanium martensite start temperature is approximately 802 °C) and by the fact that α’ martensite has the same chemical composition of the parent β phase.

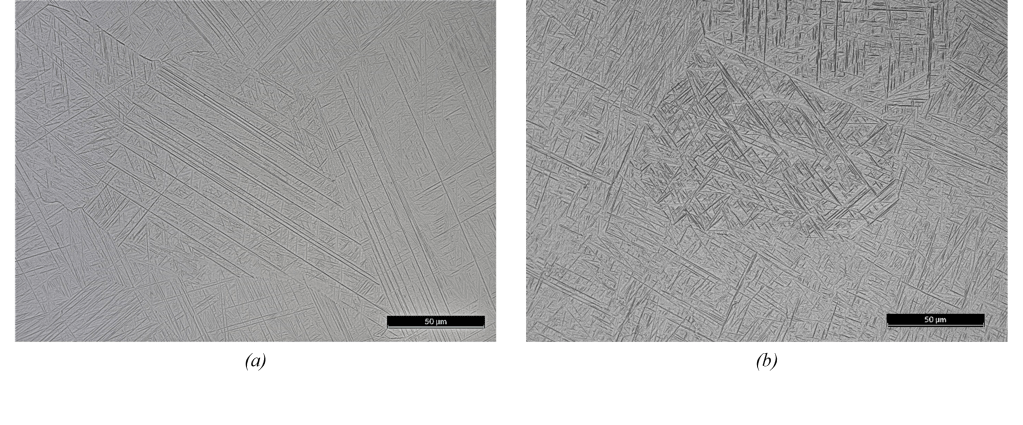

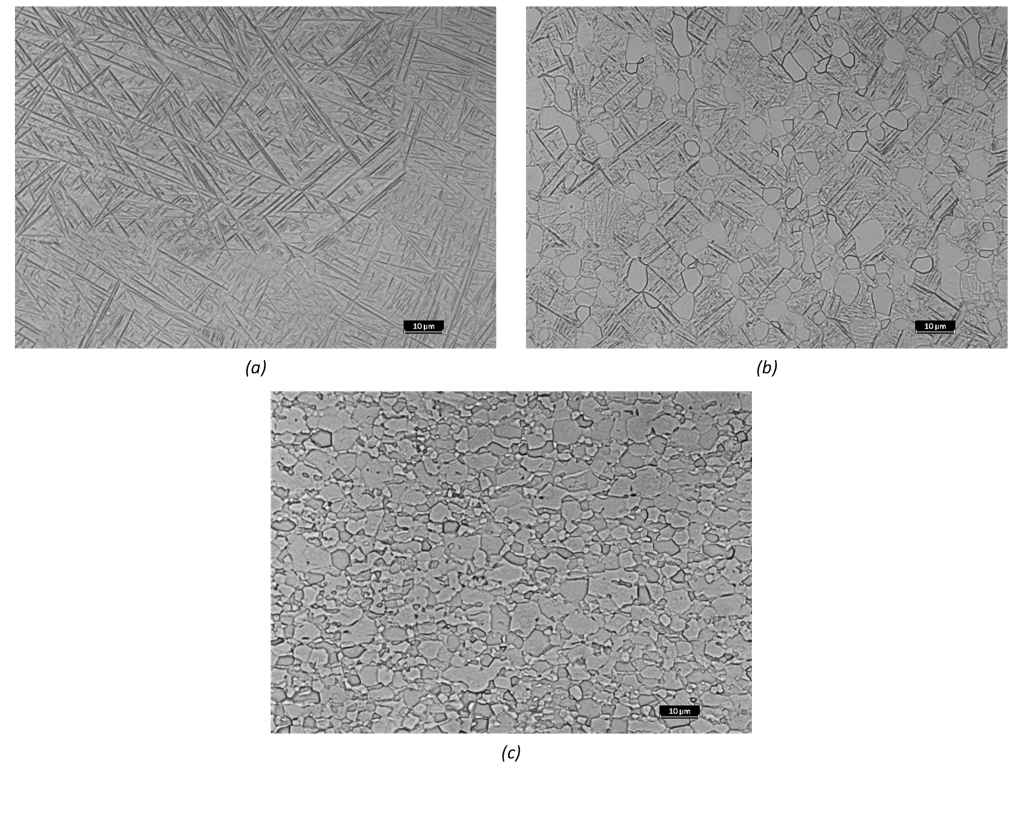

Speaking of morphology, also for titanium α’ martensite occurs in two variants, which can often coexist even in the same component, defined respectively as “lath martensite” and “plate martensite”, whose appearance under light microscope is shown in Figure 2 for Ti-6Al-4V alloy.

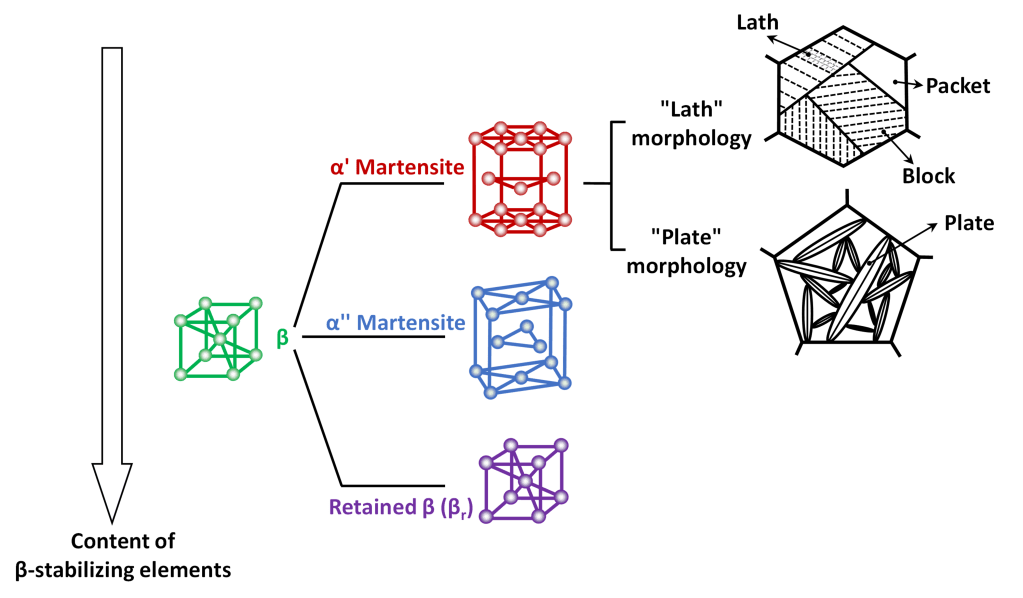

In some titanium alloys, the presence of another martensitic microstructure with orthorhombic crystal lattice, called α” (or “alpha double prime”), has also been found. As a general rule, the transition from α’ to α” martensite is determined by the content of β-stabilizing elements in the specific alloy, raising the content of β-stabilizers promotes the formation of α” instead of α’. Furthermore, as it can be seen in Figure 3, if the content of β-stabilizing elements is particularly high, martensitic transformations are completely suppressed and after quenching β-phase remains at room temperature in a metastable condition, which is commonly reffered to as beta retained (or βr).

(Magnification 500X – Metallographic etching with Kroll’s reagent).

In the metallurgical industry, the formation of martensitic microstructures is widely used for α + β titanium alloys, that is those alloys in which the chemical composition is such that at room temperature α and β phases can coexist, for significantly increasing hardness and mechanical properities.

Within this group of alloys we have the well kown alloy Ti-6Al-4V, which covers alone about 50% of world titanium production, Ti-6Al-6V-2Sn and Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-6Mo alloys.

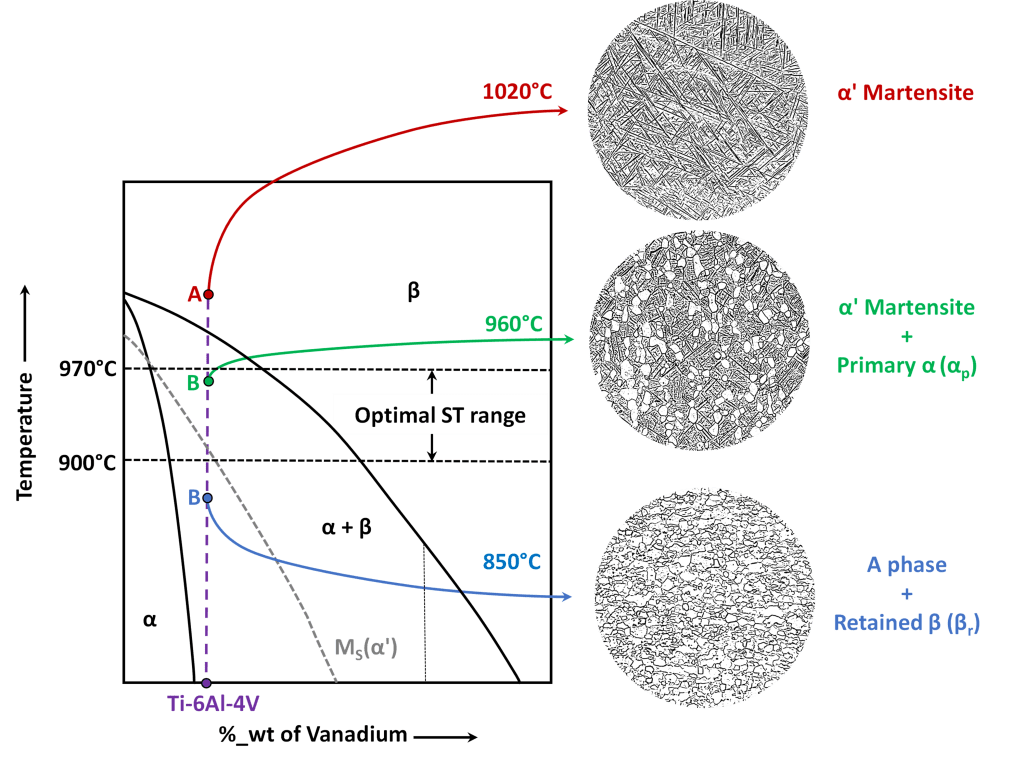

As for quenching and tempering of steel, a sequence of two heat treatments is normally performed, the former is colled solution treating, or ST, the latter aging, or A.

As far as solution solution treating is concerned, which is usually carried out by water quenching, the choice of the correct process temperature is of fundamental importance. As can be seen from Figures 4 and 5, which refer to the specific case ofTi-6Al-4V alloy, by carrying out solution trating at temperatures higher than β-transus (which is about 1000°C fot this alloy) the microstructure completely consits of α’ martensite; this condition allows to obtain the maximum hardness after the subsequent aging at the expense, however, of low values of ductility and toughness, also deriving from the excessive grain growth of the parent β phase.

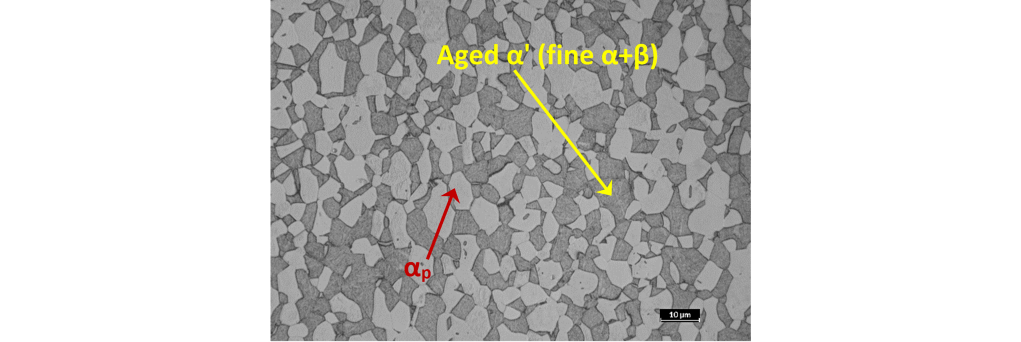

For this reason, solution treating is therefore carried out at temperatures lower than β-transus, in the specific case of Ti-6Al-4V alloy between 900 and 970°C; consequently, at the end of cooling, the microstructure consits of a matrix of hexagonal α’ martensite containing ewgular equiaxed grains of α phase, called primary alpha, or αp, whose amount decreases with increasing of solution treating temperature, until it ideally vanishes when the treatment temperature reaches β-transus tmeprature. This condition represents the targeg to be obtained after proper solution trating, as it allows the achievement of the best possible compromise between hardness, ductility and toughness after subsequnt aging.

On the other hand, if solubilization trating temperature were too low, β phase would be so enriched in β-stabilizing elements (V in the case of Ti-6Al-4V) that the martensitic transformation during cooling would not be possible; in this case the microstructure would be made up of α phase grains with retained β (or βr) and subsequent aging would inevitably produce a very modest increase in hardness, resulting of no practical interest.

(a) 1020°C: the microstructure consists of only α’ martensite; (b) 960°C: equiaxed grains of primary alpha (αp) in a matrix of α’ martensite; (c) 850°C: grains of alpha phase with a small amount of retained beta (βr).

(1000x magnification – Metallographic etching with Kroll’s reagent).

Aging, which for the Ti-6Al-4V alloy is usually performed between 480 and 650°C for times ranging from 4 to 8 hours, is the final phase of the cycle and allows a further increase in the mechanical characteristics, due to the fact that martensite decomposes into a very fine mixture of α and β phases with submicroscopic dimensions that cannot be resolved under an optical microscope, even at high magnifications (Figure 6).

(Magnification 1000x – Metallographic etching with 0.5% HF reagent).

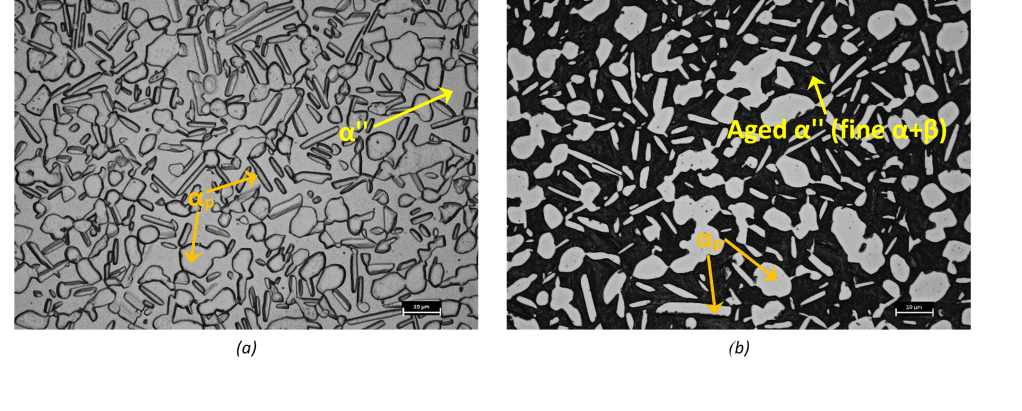

As can be seen from Figure 7, aging also produces the same effect in alloys such as Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-6Mo where, due to the higher content of β-stabilizing elements, solution treating produces the formation of orthorhombic martensite α”.

(a) after solubilisation at 850°C: microstructure consisting of primary α with both globular and elongated shape in matrix of orthorhombic martensite α”; (b) like the previous one after subsequent aging at 695°C for 4h: the martensitic matrix was transformed into a mixture of α and β (aged α”) with sub-microscopic dimensions.

(Magnification 1000X – Metallographic etching with Kroll’s reagent).

made of Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-6Mo alloy.

It’s wothy pointing out that unlike steel, in which hardening is mainly due to the presence of carbon atoms which remain trapped in the martensite lattice, titanium alloys never contain interstitial elements in such an amount as to induce a similar effect. The increase in mechanical properties, therefore, depends exclusively on the very small dimensions of the microstructural constituents and, although important and widespread in the industrial field, is therefore more limited than what is obtained in quenching and tempering of steels.

However, the combination of high mechanical characteristics, as reported in Tables 1 and 2 for Ti-6Al-4V and Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-6Mo alloys, low density (about 4.5 against 7.5 g/cm3 of steel) and excellent corrosion resistance, has made titanium alloys strengthned by solution treating and aging widespread in a variety of aerospace, energy, and biomedical applications.